How Did Theodore Roosevelt Help Save the Game of Football?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about football and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the football urban legends featured so far.

FOOTBALL URBAN LEGEND: The annual Army-Navy Game drew two separate U.S. Presidents directly into the planning of the game and, ultimately, the future of football itself.

Today, let us look back at a time when the highest elected official in the country, the President of the United States, ended the Army-Navy football rivalry nearly as soon as it began! And then marvel at how a later President both saved the rivalry and, in many ways, the game of football itself!

I don’t think that I really need to tell you that the early days of football barely resemble the game that we know today. Not that football today is exactly a gentleman’s game, but in the early days the games were played practically without rules – and without mercy. A good comparison to football in the early 1890s would be looking at professional boxing before their various rules (most famously, the Queensberry rules) were put into place – just a vicious, bloody mess. However, it was a popular vicious, bloody mess!

As the various universities in the country began to institute football programs in the 1870s (as the sport slowly evolved from rugby), the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis was one of the earliest schools to adopt the sport. The United States Military Academy at West Point did not begin to play football until 1890, which was when the Naval Academy challenged them to a game. That game in November of 1890 sparked a tradition that continues to this day, the legendary “Army-Navy Game.”

That first game was mostly a pick-up game, and it was viewed by about 500 people (as you might imagine, Navy won handedly, which would make sense seeing as how they had been playing the sport for over a decade at that point) but soon the game became a bit of a sensation. The 1893 game was attended by over eight thousand people! However, this upswing in popularity also brought with it significant drawbacks, namely that with the popularity also brought fanaticism. And when you put two opposing fanatical groups against each other, well, you might as well be flicking matches at powder kegs. The highlight/lowlight of the 1893 Army-Navy game happened when an Army-supporting brigadier general and a Navy-supporting rear admiral got into an argument over the game (which was a hotly contested low-scoring game won by Navy 6-4, bringing their record to 3-1 in the four match-ups). The argument escalated to the point where the two men decided to have a duel!!! Luckily, cooler heads prevailed and the duel was called off, but still, in many ways, the damage was done.

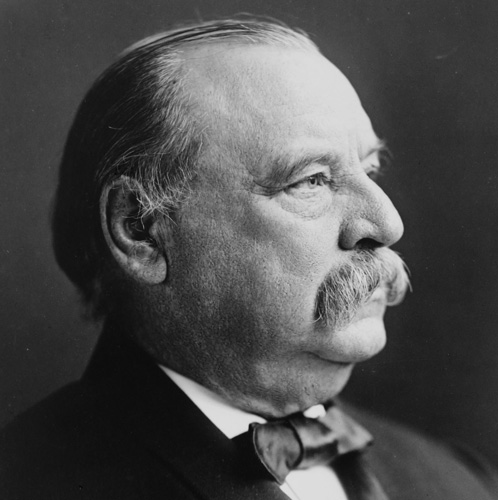

In February of 1894, President Grover Cleveland actually called a special cabinet meeting to discuss the Army-Navy Game. By this point, the superintendent of the Military Academy, Oswald Ernst, had already conducted his own investigation into football at West Point. Ernst was an old school military man (he was a Civil War veteran, even!) and he found the notion of his cadets careing so much about football games to be unsettling, but he ultimately determined that the games did no real harm – except, of course, the Army-Navy Game, which he found to be a “bad influence” and that the excitement over the game was far too out of control. He recommended to the Secretary of War, Daniel S. Lamont, that the games be cancelled in the future. So, at the cabinet meeting, Lamont brought this to the attention of the others present and by the end of the meeting, Lamont and Secretary of the Navy Hillary A. Herbert agreed to end the rivalry.

How they did it was a bit interesting. Rather than outright canceling the game, they both just issued general orders that both the Military Academy and the Naval Academy could only play football games at their home fields. Since neither could go on the road, well, then they very well couldn’t play each other, now could they?

So it went for a number of years. Even though Army and Navy could not play each other, their respective programs still continued to grow and the sport became more and more popular. In August 1897, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy made an impassioned plea to the Secretary of War to allow the game to resume.

Here is the text of that letter:

My dear General Alger:

For what I am about to write you I think I should have the backing of my fellow-Harvard man, your son. I should like very much to revive the football games between Annapolis and West Point. I think the Superintendent of Annapolis, and I dare say Colonel Ernst, the Superintendent of West Point, will feel a little shaky because undoubtedly formerly the academic routine was cast to the winds when it came to these matches, and a good deal of disorganization followed. But it seems to me that if we would let Colonel Ernst and Captain Cooper come to an agreement that the match should be played just as either eleven plays outside teams; that no cadet should be permitted to enter or join the training table if he was unsatisfactory in any study or conduct, and should be removed if during the season he becomes unsatisfactory; if they were marked without regard to their places on the team; if no drills, exercises or recitations were omitted to give opportunities for football practice; and if the authorities of both institutions agreed to take measures to prevent any excesses such as betting and the like, and to prevent any manifestations of an improper character—if as I say all this were done—and it certainly could be done without difficulty—then I don’t see why it would not be a good thing to have a game this year.

If you think favorably of the idea, will you be willing to write Colonel Ernst about it?

The letter must have worked, because in 1899, during President William McKinley’s first term as President, the game resumed. The solution to the heated rivalry was that the games would be held at a neutral site. Franklin Field in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was chosen and the rivalry was renewed!

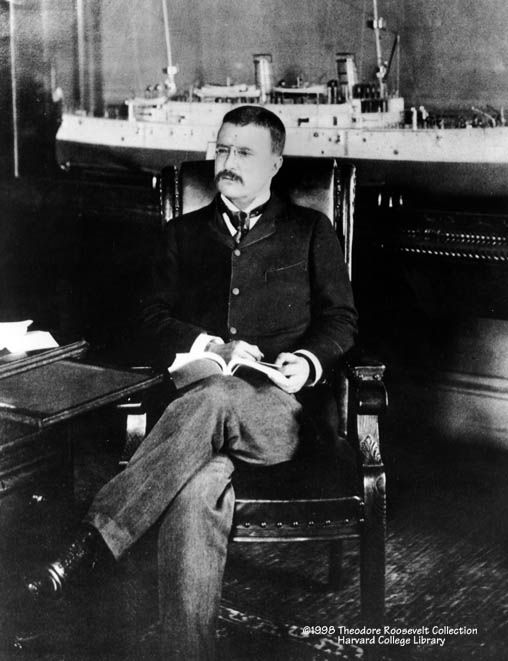

McKinley ran for President again in 1900, and as his running mate, guess who he chose? The same fellow who wrote the above cited letter, a gentleman you might have heard of named Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1901, now President himself (due to McKinley’s tragic assassination earlier that year), Roosevelt instituted the tradition of the President (when attending the Army-Navy Game) of watching the game from different sides of the field for each half, thereby splitting his support between the two teams (this was a bit unconvincing when future President Dwight D. Eisenhower attended games, as he was a graduate of West Point – he actually played in the game for Army in 1912!).

In 1905, Roosevelt once again came to the aid of football. You see, while concerns were alleviated about the conduct in football games in the short term in 1899, by 1905 they had returned with a vengeance! Football was considered just far too violent. Nineteen collegians were killed in football games in 1905 alone! Heck, Roosevelt himself had a personal stake in the issue, as his son Ted (who he mentioned in the letter above) had his nose broken playing for Harvard in a football game that year. There were some calls to ban the sport entirely at schools. Roosevelt, though, felt a better solution would be to simply regulate it.

So in October of 1905, he called together at the White House the presidents of five major institutions (Army, Navy, Harvard, Princeton and Yale) and had them form the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS), which was officially established in March of 1906. That organization later changed its name in 1910 to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), which is what it remains called to this day. The policies determined by the NCAA would change the game of football forever, both college football and, by osmosis, the burgeoning professional game, allowing them to become the mainstays of American culture they are today.

Thanks, TR!

The legend is…

STATUS: True

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future installments! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com