What Rule Change Kept Famed Pulp Novelist Zane Grey From Ever Playing Professional Baseball?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about baseball and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the baseball urban legends featured so far.

BASEBALL URBAN LEGEND: Amos Rusie and Cy Young helped to keep Zane Grey from becoming a major league pitcher.

Pearl Zane Grey (better known as just Zane Grey) was one of the most prolific and popular pulp novelists of the 20th Century. His books have been adapted countless times for films and TV (he even had a TV series in the late 1950s based just on his stories), with perhaps his The Riders of the Purple Sage being his most popular story (both in terms of popularity with fans and with amounts of times adapted into other media).

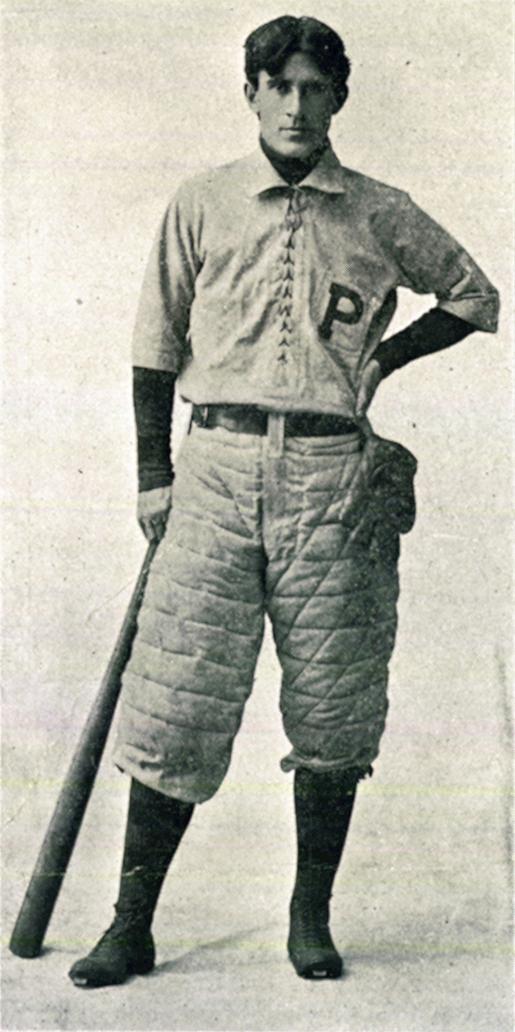

Grey’s path to literary stardom was a circuitous one, though, and it was one that might have gone an entirely different way had it not been for the abilities of the best pitchers of the early 1890s, Amos Rusie and Cy Young in particular. How did these two future Hall of Famers alter the path of Zane Grey’s life? Read on to find out!

In the early days of professional baseball, the official rules of the game were more than a bit nebulous. In a lot of ways, they were making things up as they went along. Heck, until 1894, foul balls did not even count as strikes (imagine the tedium of watching an at-bat with today’s batters if foul balls did not count as strikes! Bobby Abreu’s at-bats would take two hours!)! Mostly, as was the case with the foul balls as strikes rule, the rules would change in response to what was seen as a negative situation (in the case of foul balls not counting as strikes, it was the annoyance of batters just sitting there fouling ball after ball just trying to get the pitcher to eventually throw four balls for the walk). In the original official rules of baseball that was agreed on upon the formation of the National League (NL) in 1876, the pitching mound (it was barely even a mound back then, perhaps best to just call it the pitching rubber) was 45 feet away from home plate. This worked for a few years, but by 1880, pitching had developed to the point that 45 feet was just way too close. The batting average in the National League dropped to .245 as a league, down from .265 in the first year of the NL. So in 1881, the mound was moved five feet backwards to 50 feet.

This, too, worked out well for awhile, but through the 1880s, things began to change once again as pitchers adjusted to the new distance. Batting averages actually dipped below .245 in 1885, and in 1887 the rules were changed again. The pitching rubber was, in effect, shaped like a box. Pitchers were allowed to pitch from the front part of the box (50 feet away) but in 1887 that was changed so that they had to pitch from the back end of the box (55 feet 6 inches away).

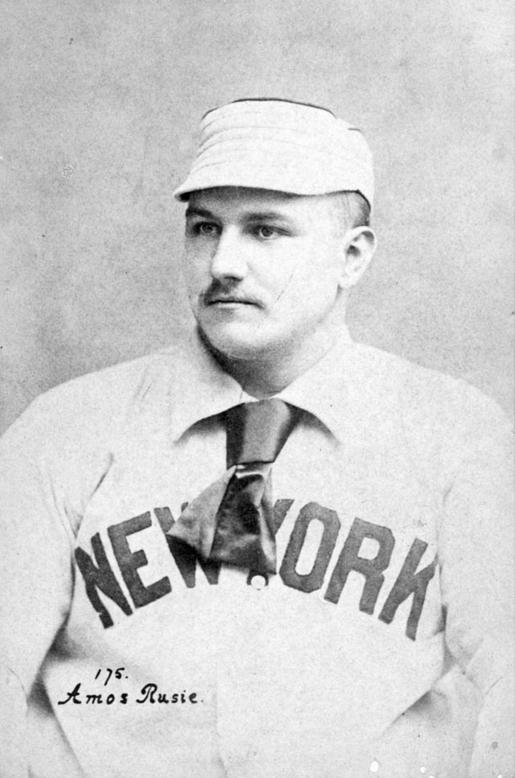

Batting averages skyrocketed, but very soon, they began fluctuating again. Heck, in 1888, the league batting average dipped under .240 entirely!!) In 1892, after the league batted .245 once again as a whole, the rules committee decided to change things again. However, this time around, it was not just the league’s batting average as a whole (because, after all, as I mentioned, they had hit below .240 just a few years earlier), but rather because of the physical capabilities of some of the current crop of pitchers, most prominently the aforementioned Amos Rusie and Cy Young.

Rusie and Young were both dominant fastball pitchers (although no radar guns existed at the time, it seems believable enough that both men were hitting 90 miles per hour). Rusie reached the National League one year ahead of Young, in 1889, and he was an instant sensation. Hailing from Indiana, Rusie was quickly dubbed “The Hoosier Thunderbolt,” and by the end of the 1890 season (which he played for the New York Giants) he was a pop culture phenomena. There was even a book released about him titled Secrets of Amos Rusie, The World’s Greatest Pitcher, How He Obtained His Incredible Speed on Balls.

Denton True Young joined the NL the next year for the Cleveland Spiders, and became a sensation himself. While there is a bit of a debate over the origin of the “Cy” nickname, Young believed (and I think I tend to believe it, as well) that it came from the speed of his pitches, as they seemed like a “cyclone,” which became his nickname before being shortened to “Cy” (the alternative theory is that he was nicknamed “Cyrus” by his teammates because of his rural upbringing).

While there had been plenty of dominant pitchers in the National League ever since it began, Rusie and Young stood out not just for their pitching acumen, but for their physical size. Rusie was second in the league in strikeouts in 1892 (Young was tenth). Take a look at the dimensions of the other four pitchers in the top five in strikeouts:

5′ 9″, 175 pounds

5′ 10″, 145 pounds

5′ 10″, 175 pounds

5′ 11″, 170 pounds

Rusie was 6″ 1′, 200 pounds and Young was 6″ 2′, 210 pounds!! They were imposing physical specimens for the time.

So it was largely the fear of these lumbering pitchers with their blazing fastballs that led the league to push the mound back even further. Rusie’s beaning of future Hall of Famer Hughie Jennings in 1892 also led to the natural level of concern over their fastballs – Jennings was comatose for four days before recovering – this only strengthened the belief that batters were being put in harm’s way to have the pitcher stand so close.

So the league announced the pitching rubber to be pushed back 60 feet 6 inches, which is where it remains to this day. Amusingly, to counter this effect, the Giants began to raise the rubber into the air (as there was no rule saying how high the rubber could be) to give the towering Rusie an even bigger advantage. Other teams with tall pitchers followed suit, and eventually a standard height for the pitching mound was forced to be determined by the league (decades later, the next time the rules were changed to adjust for pitching dominance was a lowering of the height of the mound in the late 1960s).

What does this have to do with Zane Grey?

Well, Grey was a fine baseball player himself. Born in Zanesville, Ohio (named after an ancestor of his), Grey and his brother Romer were athletic young men who played a good deal of baseball. It was while playing summer baseball for the semi-pro team the Columbus Capitals in the early 1890s that Grey was first discovered by baseball scouts. He was offered a baseball scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania, which he began attending in 1892 in the pursuit of becoming a dentist (like his father before him).

Grey was a decent hitter, but his primary skills were as a pitcher. He had a great curve ball that had a lot of break to it, and it would often fool hitters. Grey did not have a particularly strong arm, so he would have to fool hitters to get them out, but he was very good at it. Well, two years into his college career, the changes to the professional baseball rules came into effect in the Ivy Leagues, as well. The new 60 foot 6 inch distance was too much for Grey’s arm, and he was finished as a pitcher. He was moved to the outfield, where he was still a decent enough player. He was good enough that he did still consider the possibility of trying to pursue a major league career upon graduating from Penn in 1896, but he eventually deemed it impractical and became a dentist instead. His brother Romer continued to play professional baseball and even made it to the Majors for a cup of coffee in 1903!

While working as a dentist, Grey began to explore his boyhood love of reading and writing, and he had his first story published in a magazine in 1902. Up until this point, he had continued to play amateur baseball in the summer, but when his writing career began to develop he dropped the sport. By the end of the Aughts, Grey had slowly but surely begun to see more of his work published, including his first few novels. In 1912, Riders of the Purple Sage was released to widespread popular acclaim and high sales and Grey became a publishing star, leading to a long and storied career where he was one of the first authors to make a million dollars off of his work (his books sold over 20 million copies during his lifetime). His love of baseball remained, though, as he wrote a couple of novels about baseball.

He passed away in 1939 as one of the most beloved authors in the country, but never a professional baseball player, a path determined by a rule change over forty years later caused by a Thunderbolt and a Cyclone.

Thanks to Thomas H. Pauly’s nifty biography of Grey, Zane Grey: His Life, His Adventures, His Women, for much of the information for this piece!

The legend is…

STATUS: True (in a roundabout way)

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future installments! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com.