Did a Hall of Famer Really Leave a Letter to be Opened After His Death Revealing Whether He ACTUALLY Made a Famous Catch?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about baseball and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the baseball urban legends featured so far.

BASEBALL URBAN LEGEND: A Hall of Famer revealed the truth behind a famous catch in a letter only to be read after his death.

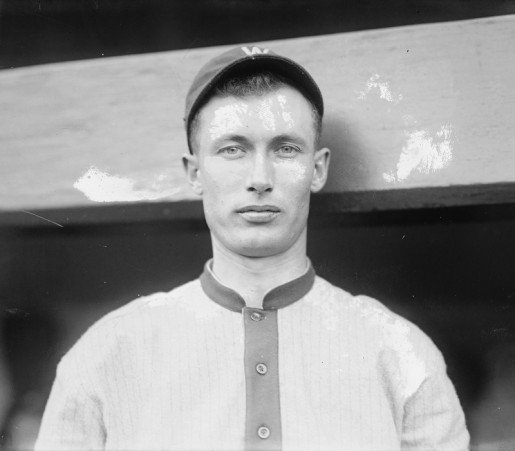

On October 13, 1974, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer Sam Rice passed away at the age of 84. His death came almost exactly 49 years after Game Three of the 1925 World Series (October 10, 1925). In that game, Rice made one of the most famous catches in World Series history.

It was also one of the most controversial catches. The controversy surrounded whether Rice ACTUALLY made the catch. Since the play involved Rice being out of everyone’s field of vision for at least ten seconds, only Rice knew the answer for sure. Rice always actively avoided telling people the truth (not even his own wife and children), and legend had it that Rice had written a letter for the Baseball Hall of Fame containing the truth that was not to be opened until his death.

Well, two weeks after Rice died, there was no such letter. Cliff Kachline, the official historian of the Baseball Hall of Fame, said “That Sam Rice letter has been a rumor for a long time, but we never had any solid evidence there was one.”

Was there a letter?

Sam Rice began his Major League career in 1915 as a 25-year-old relief pitcher for the Washington Senators. He would on to play a remarkable 18 seasons as a member of the Senators. However, his fame came not as a pitcher but as an outfielder. In 1916 he was converted to the outfield and he spent the rest of his career as a speedy outfielder. He had range like you wouldn’t believe and he was one of the best defensive outfielders in the American League during the early 1920s. He was a very similar hitter to Rod Carew – mostly a singles hitter but his speed would often turn those singles into doubles. His career batting average was .322. He ended his career in 1934 with a one-year stint with the Cleveland Indians. The 44-year-old Rice finished just 13 hits shy of 3,000, a fact that he later revealed was unknown to him at the time or else he would have stuck around to get those hits. In fact, a year or so later, Clark Griffith (owner of the Senators) offered to bring Rice back to the Senators just to get the hits. Rice thanked him for the generous offer but noted that he was out of shape and did not feel it worth it. Rice has the most hits of any player not to reach 3,000 hits.

Rice won a World Series championship with the Washington Senators in 1924 (defeating the New York Giants in seven games with the great Walter Johnson winning Game 7). The following year, the Senators were in the Series again, this time matched up against the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Senators would lose this series in seven games, as well (with Johnson this time taking the loss in one of the worst playing conditions the World Series has ever been played in – there were so many delays due to bad weather that Game 7 was “forced” to be played in a foggy downpour). However, the Senators had a classic victory in Game 3. The Senators took a 4-3 lead in the bottom of the seventh inning with a single by the slow-moving rightfielder Joe “Moon” Harris. The Senators player-manager Bucky Harris then removed Harris for a defensive replacement in the eighth inning. Harris had Rice move from center to right and had Earl McNeely come in to play centerfield. After two outs in the top of the eighth inning, the Pirates’ catcher, Earl Brown, seemed like he was about the tie the game up with a booming drive to right field. Harris’ defensive change looked brilliant, though, as Rice raced to right field (where temporary bleachers had been set up) and managed to dive for the ball, falling behind the bleachers. At least ten seconds passed before McNeely pulled Rice out of the stands – with the ball clutched firmly in Rice’s glove. The umpires ruled that it was a catch and the Washington fans were elated while the Pittsburgh bench was irate. Pittsburgh manager Bill McKechnie insisted that the ball had to have fallen out of Rice’s glove when he hit the fence and that someone (Rice even) must have just put the ball into his glove from behind the stands when he was out of sight. The umpires still kept it as an out. And obviously, this being 1925, there were no replays to prove it either way.

Rice was besieged by requests for the truth of the matter. Magazines, newspapers, he could have made a good deal of money out of telling his story. Instead, he went with “the umpire said I caught it.” This was his only statement on the topic for decades. Again, he would not even tell his wife or kids the truth. Once Rice was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1963, though, the demand for the answer increased. Every time he would attend a Hall of Fame event, Lee Allen, then-historian of the Hall of Fame, would pester Rice to at least write a letter that the Hall could keep when Rice passed away. By this point in time, by the way, fellow Hall of Famer Bill McKechnie had changed his tune and now thought Rice HAD made the catch (winning the 1925 World Series probably made McKechnie a good deal more magnanimous about the catch). Rice gave McKechnie the impression that he would go along with Allen’s recommendation. In addition, Rice’s wife recalled that Rice told her he was going to do what Allen asked of him.

The problem came in 1974 when Rice passed away and no one could find the darned thing! Some felt that Allen must have had it, but Allen had died a few years earlier, as well. Things looked bleak and, as I stated earlier, the Hall of Fame itself was ready to chalk it up to an urban legend (despite Rice’s widow insisting that her husband HAD written the letter in question). Luckily, as it turned out, the letter was not with the Hall of Fame but at the Manhattan office of Hall of Fame president Paul S. Kerr, who somehow had not realized that people were looking for the letter that was in his possession (which is weird, since he attended Rice’s funeral). Kerr made a bit of a ceremony out of the opening of the letter at his Wall Street office. It was like the reading of a will!

The letter was dated Monday, July 26, 1965 and it read:

It was a cold and windy day; the right field bleachers were crowded with people in overcoats and wrapped in blankets, the ball was a line drive headed for the bleachers towards right center, I turned slightly to my right and had the ball in view all the way. Going at top speed and about 15 feet from [the] bleachers jumped as high as I could and back handed and the ball hit the center of pocket in glove (I had a death grip on it). I hit the ground above five feet from a barrier about four feet high in front of the bleachers with all my breaks on but couldn’t stop so I tried to jump it to land in the crowd but my feet hit the barrier about a foot from top and I toppled over on my stomach into first row of bleachers, I hit my Adams apple on something which sort of knocked me out for a few seconds but [Earl] McNeely arrived about that time and grabbed me by the shirt and pulled me out. I remember trotting back toward the infield still carrying the ball for about halfway and then tossed it towards the pticher’s mound. (HOw I have wished many times I had kept it).

At no time did I lose possession of the ball.

Sam Rice.

That certainly answers the question of whether Rice actually left a letter!

The legend is…

STATUS: True

Thanks to Jeff Carroll’s neat (and aptly-titled), Sam Rice: A Biography of the Washington Senators Hall of Famer for the information for this piece. And thanks to one of my pals at the Replacement Level Yankee Weblog, kronicfatigue, for inspiring me to feature this legend.

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future installments! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com.