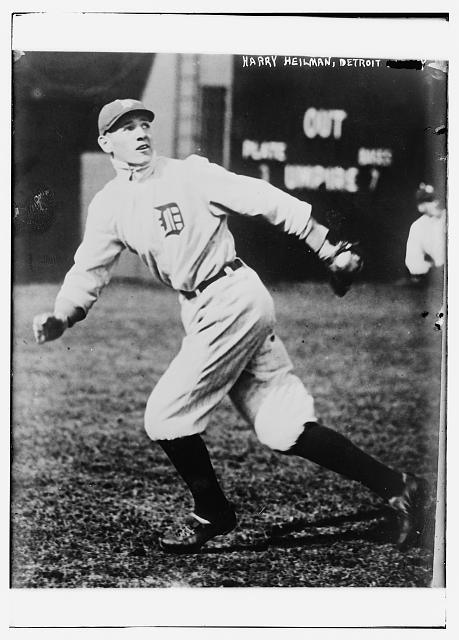

How Did a Bookkeeper Who Had Never Played Organized Baseball Become a Hall of Famer?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about baseball and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the baseball urban legends featured so far.

BASEBALL URBAN LEGEND: A series of fortuitous events turned an 18-year-old bookkeeper who had never played organized baseball into a Hall of Famer.

With the fact that both Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams, two of the best baseball players of the 1940s (or really any decade), hailed from California, it is somewhat easy to forget that in the early days of professional baseball, California was a bit of a no man’s land. From the beginnings of professional baseball up through the first quarter of the 20th Century, baseball did not venture much further west than St. Louis. Of the first 39 inductees into the Hall of Fame, the furthest west any of them were born were a fellow we talked about last week, Grover Cleveland Alexander, who was born in the middle of Nebraska (two other players were born in Kansas and Texas, respectively, but both were on the far east sides of their states).

The first California-born player to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame was the fortieth inductee, Frank Chance (of “Tinker to Evers to Chance” fame).

So the geographical odds were already against San Francisco native Harry Heilmann, and yet, through a series of fortuitous breaks that occurred when he was 18 years old (and working as a bookkeeper) Heilmann made his way from never playing organized baseball to being a professional ballplayer, then a Major Leaguer and, eventually, a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Harry Heilmann was born in 1894 in San Francisco, California. He attended Sacred Heart High School (the same school that future Hall of Famer Joe Cronin later attended). Interestingly enough, Heilmann did not play baseball in high school. While there was a dearth of major league players from California, the sport was still quite popular in the state. In fact, Heilmann’s older brother, Walter, was an acclaimed pitcher whose career (and life) was cut short when he died in a boating accident. I have seen conflicting reports on whether Heilmann chose not to play high school baseball or whether he just could did not make the team (shades of the story of Michael Jordan getting cut by his high school basketball team, a legend I’ve explored in the past here). Whatever the case may be, Heilmann played football, track and field and basketball (he was All-State as a basketball player) but not organized baseball (although he certainly played baseball for fun).

In 1913, Heilmann was almost 19 years old and he was working as a bookkeeper for the Mutual Biscuit Company in San Francisco when a former classmate from Sacred Heart asked Heilmann if he would fill in for him during a semi-pro game in Hanford, California (in the San Joaquin Valley). Often, this story mentions that the game was part of the San Joaquin Valley League, but I am not sure if that’s absolutely true (the San Joaquin Valley League had a Hanford team, I just don’t know if it was in operation in 1913), but suffice it to say that it was a semi-professional baseball game in Hanford, California. For the game, Heilmann was paid $10.

Unbeknownst to Heilmann when he agreed to fill-in was that that game would change his life forever.

You see, Heilmann won the game with an eleventh-inning double, and that (and presumably the rest of his play during the game) drew the interest of a scout from the Northwest League, who signed Heilmann to a professional contract to play for the Portland Beavers. Years later, Heilmann would recount that they treated him to a spaghetti dinner as a “signing bonus.” The Northwest League was pretty much the lowest professional league you could be a part of at that point in time (it should not be confused with the Single-A Northwest League that exists to this day). You see, the Northwest League (now known as the Pacific Coast International League) was the minor leagues of the minor leagues. These Portland Beavers were the farm team for the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League which, of course, was itself a minor league for the Major Leagues. However, in the 1910s, the Pacific Coast League was the league in California.

So Heilmann began to play for the Portland Beavers, and his professional career got off to a rousing start with an 0 for 3 outing and an error at first base. By the end of the year, however, he hit over .300. Luckily, Fielder Jones (the president of the Northwest League) recommended Heilmann to Frank Lavin, owner of the Detroit Tigers. In September of 1913, the Tigers “drafted” Heilmann from the Beavers, paying a figure between $700 and $1,500.

Heilmann performed well for Detroit in Spring Training for the 1914 season, but during the year itself the 19 year old played pretty dreadfully. He hit .225 and, perhaps more importantly, played awful defense in the outfield (Heilmann was never the fastest fellow, eventually earning himself the nickname of “Slug,” so the outfield was probably not the best place for him), including one remarkable game where he committed three errors in a single inning, including pretty much each of the three possible errors that an outfielder can commit (he fumbled a single, allowing the runner to reach second, he then overthrew the second baseman to allow the runner to reach third and later dropped a fly ball)!

Detroit made a deal with Heilmann’s hometown San Francisco Seals, of the Pacific Coast League. The Tigers would release Heilmann to the Seals for the 1915 season under the condition that they would get him back after the season was through (and they promised not to recall him during the 1915 season).

Heilmann performed well for the Seals and was back in the Majors in 1916, playing all over the diamond (first base and all three outfield positions). Perhaps his most notable achievement that season was when he saved a young woman from drowning when the car her father was driving drove off of a cliff. Heilmann dove in and saved her, a heroic act that had to be even more inspiring knowing that his brother died from drowning.

Heilmann acquitted himself nicely as a hitter in 1916-1918, hitting between .276 and .282 all three years (he missed half of the 1918 season to World War I. He served on a submarine). In 1919, though, his career really began to turn around as he hit .320. Amazingly, though, his career really changed in 1921 when Heilmann’s legendary teammate, Ty Cobb, became his manager (Cobb continued to play, as well). Despite being teammates for over five years before becoming manager of the Tigers, Cobb never gave Heilmann advice on hitting, even though Cobb had discovered numerous correctable flaws in Heilmann’s hitting stance years earlier. Cobb would later claim that he did not feel right giving advice to a peer, but when he was the manager, that was his job, so he did so.

Whatever Cobb’s motivations, the results paid off immediately. Heilmann hit .309 in 1920. In 1921, he hit .394!!! Heilmann’s prowess surprised even Cobb, who came in second to Heilmann that season (and was not pleased about it). Not only was Heilmann hitting for average, but he was now hitting for power, as well, slugging over .600!

From 1921 through 1927, Heilmann hit a collective .380, including an astonishing .403 in 1923. From 1921 through 1927, Heilmann led the league in batting in each of the odd seasons, for four titles in total. Since Heilmann was under a series of two-year contracts, people, including Heilmann himself, used to joke that he would put in extra effort in his contract years, hence the higher averages. That was just a joke, of course, as Heilmann’s “off” years were still amazing (again, he hit a collective .380 from 1921-1927).

The Tigers sold Heilmann to the Cincinnati Reds after the 1929 season, as he had begun to suffer from arthritis in both of his hands. He had one last great season for the Reds in 1930, hitting .335, before the arthritis was just too much for him and he skipped the 1931 season entirely. He tried a comeback in 1932, but he retired for good after hitting .258 in 15 games for the Reds.

Heilmann became a play-by-play announcer for the Tigers radio broadcasts from 1934 until his retirement in 1950, when lung cancer forced him to retire. His former teammate Cobb valiantly stumped for Heilmann to be elected to the Hall of Fame before he passed away, but he came up just short for election in 1951. He died in July of 1951. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in January of 1952, the sixty-first member of the Hall and only the second California native (heck, in between Chance and Heilmann there had only been two other players born west of St. Louis, and both just barely so).

A pretty amazing career for a guy who was a bookkeeper for a biscuit company before ever playing organized baseball, huh?

The legend is…

STATUS: True

Thanks to Mike Lynch and Dan D’Addona for their tireless research efforts that provided much of the information about Heilmann in this piece.

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future installments! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com.