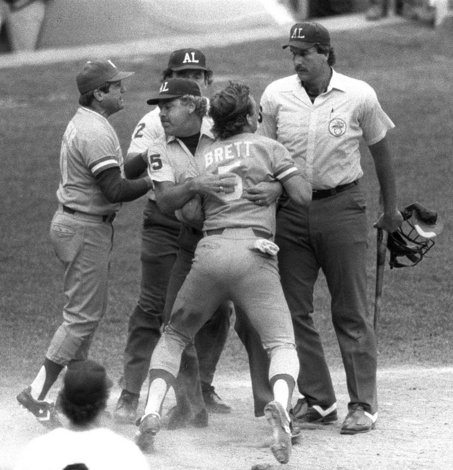

Did Lee McPhail Go Against the Written Rules When He Made His Ruling in the “Pine Tar Game”?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about baseball and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the baseball urban legends featured so far.

BASEBALL/MUSIC URBAN LEGEND: American League President Lee MacPhail went against the letter of the law when he overturned the umpire’s decision in the famous “Pine Tar Game.”

It seemed like the entire sports world was shocked on June 2, 2010 when Detroit Tiger pitcher Armando Galarraga seemed poised to pitch a perfect game (which would have been a record three in one year, following Oakland’s Dallas Braden and Philadelphia’s Roy Halladay). After retiring the previous 26 Cleveland Indians, the 27th man to face Galarraga, rookie shortstop Jason Donald, hit a grounder that was fielded by Tiger first baseman Miguel Cabrera, who threw to Galarraga covering first base. The ball went into Galarraga’s glove a good full step before Donald touched first base, and yet first base umpire Jim Joyce missed the call, calling Donald safe and turning Galarraga’s perfect game into perhaps the most famous one-hitter in baseball history (as Galarraga promptly retired the 28th batter to finish the game).

After the game, many fans and sportswriters wished for Major League Baseball (MLB) Commissioner Bud Selig to overturn Joyce’s call and rule Galarraga’s game an official perfect game. Whether one agrees with that position or not, I think it’s important to note the misconceptions that exist with the major example cited by most of these fans and sportswriters – American League President Lee MacPhail’s decision in the (im)famous 1983 “Pine Tar Game.”

The Pine Tar Game is the shining beacon that pretty much all sportswriters (or fans) will point to when they wish to make an argument about why a sports league should make a certain decision that, while not necessarily according to the rules of the game, seems to be the “fair” decision. In the National Basketball Association (NBA), the Pine Tar Game was cited during the 1996-97 Playoffs as well as the 2006-07 Playoffs, when key players of two teams (the New York Knicks and Phoenix Suns, respectively) were suspended due to a rule stating that players cannot leave their bench during an altercation on the court. The rule is clear on that point, but sportswriters would compare the situation to the Pine Tar Game and ask for the NBA Commissioner David Stern to make the same decision that Lee MacPhail did in 1983, and look past the rule and let the players play (in both instances, Stern chose not to).

But exactly what decision did MacPhail actually make?

The famous New York Daily News columnist Mike Lupica described the Pine Tar Game in a June 3, 2010 column about why Selig should overturn Joyce’s call:

Overturning Joyce’s call would not have made the stars fall out of the sky or made the earth stop spinning on its axis. This would have been a proud variation of what Lee MacPhail, then the American League president, did with the Pine Tar Game, Yankees vs. Royals, back in the 80s.

You remember the game. George Brett hit a home run with a bat that had too much pine tar on it. Technically, the umpires were right, going by the letter of the law, to take what turned out to be a game-winning home run from Brett out of the stands.

MacPhail said no.

He invoked the spirit of the law in sports, not the letter of it. He said that the rule about pine tar HADN’T been written to take game-winning home runs out of the stands. The home run stood. You bet it did. The Yankees and Royals came back later on a Monday afternoon and finished the game, which the Royals did end up winning.

Lupica’s take on the game echo many fans and sportswriters. But is that really an accurate description of the Pine Tar Game? I don’t believe it is.

To highlight two sentences – “Technically, the umpires were right, going by the letter of the law, to take what turned out to be a game-winning home run from Brett out of the stands” and “He [MacPhail] invoked the spirit of the law in sports, not the letter of it.”

What exactly was the “letter of the law”?

At the time, the applicable rule was 1.10 (b) (since re-labeled 1.10 (c), along with a note specifically citing the Pine Tar Incident):

The bat handle, for not more than 18 inches from the end, may be covered or treated with any material or substance to improve the grip. Any such material or substance, which extends past the 18-inch limitation, shall cause the bat to be removed from the game.

That’s all that Home Plate Umpire Tim McClelland had to work with. The “letter of the law” simply noted that the bat shall be removed from the game. It says nothing else beyond that. It does not say that you should nullify a hit by a batter with too much pine tar on it, it does not say that you should call a batter out who uses a bat with too much pine tar on it, it does not even say that you could do either of those things.

The precedent did exist, though, for an umpire calling a batter out who used too much pine tar on his bat. In a July 19, 1975 game between the New York Yankees and the Minnesota Twins (a game the Yankees ended up losing 2-1), the Yankees catcher Thurman Munson had an RBI single taken away when he was called out by Home Plate Umpire Art Frantz for using too much pine tar on his bat. Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles claims that the incident actually led to him informing Yankee Manager Billy Martin about the rule and that the Yankees could most likely achieve a similar result if they chose to with Brett, who they all knew had been using too much pine tar on his bat during the 1983 season. Martin naturally sat on this information until he had a perfect opportunity to nullify a Brett hit.

So after the Brett home run and McLelland noting that Brett’s bat did, in fact, violate Rule 1.10 (b), Martin compelled McLelland to use the 1975 precedence to invoke Rule 9.01(c), which states “Each umpire has authority to rule on any point not specifically covered in these rules.” And McLelland did so, ruling Brett out and the home run taken away.

MacPhail’s dispute, then, was not with the “spirit” of the law, but rather McLelland’s interpretation of the “letter” of the law of Rule 1.10 (b). The pine tar rule was developed not because extra pine tar gave batter’s an added advantage on hitting the ball (it did not, as the excess pine tar would not even touch the batter’s gloves) – the rule was developed because the league did not want bats to be so covered by pine tar that the baseballs would be ruined by all the excess tar (as any baseball coming into contact with tar would be rendered unusable). It was a rule designed to save money on baseballs, not to correct a performance advantage. Therefore, MacPhail ruled that calling a batter out for using such a bat was beyond the intent of the rule as written – not so much the “spirit” of the rule as much as how the rule was written and that McLelland went beyond his discretion by ruling Brett out – the penalty was disproportionate for the “crime” (which, again, was a simple matter of not wanting to see baseballs ruined by tar). Granted, MacPhail did specifically use the term “spirit of the restriction” in his ruling, so that ended up being what people remembered from the incident.

In the end, though, the much-cited Pine Tar Game was about a mis-applied (in the eye of the American League President) rule, not about a man looking beyond a rule to make the “fair” decision, which is exactly how it often referred to today, including by Mr. Lupica.

As an aside, in an amusing game of “cat and mouse,” when MacPhail ruled that the rest of game was to be played from Brett’s home run on twenty-five days after the original game, Martin decided to pull another gambit – besides mocking the game a bit by having starting pitcher Ron Guidry play center field and first baseman Don Mattingly play second base (becoming the first left-handed fielder to play second base in well over a decade), Martin also protested that Brett did not touch first base, second base or third base during his home run trot, under the theory that since it was a different umpiring crew, how could they possibly know for sure that he did? Head Umpire Davey Phillips countered this move by producing a signed affidavit by the previous umpiring crew stating that they saw Brett touch all the bases.

In any event, whether sportswriters and fans are correct in their recollection of MacPhail’s decision in the Pine Tar Game, it did not matter to Bud Selig, who determined not to overturn Joyce’s call at first base (and thereby earning himself the “Worst Person in the World” distinction by Keith Olbermann on the June 3, 2010 edition of Countdown with Keith Olbermann).

The legend is…

STATUS: False

Thanks to Mike Lupica and the Daily News for the quotes! And thanks to Major League Baseball’s rule book for the rules!

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future installments! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com.