Was Bill Russell Traded for the Ice Capades?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about basketball and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the basketball urban legends featured so far.

BASKETBALL URBAN LEGEND: The Rochester Royals passed on Bill Russell in the 1956 NBA Draft because the Boston Celtics arranged for the Royals to get the Ice Capades.

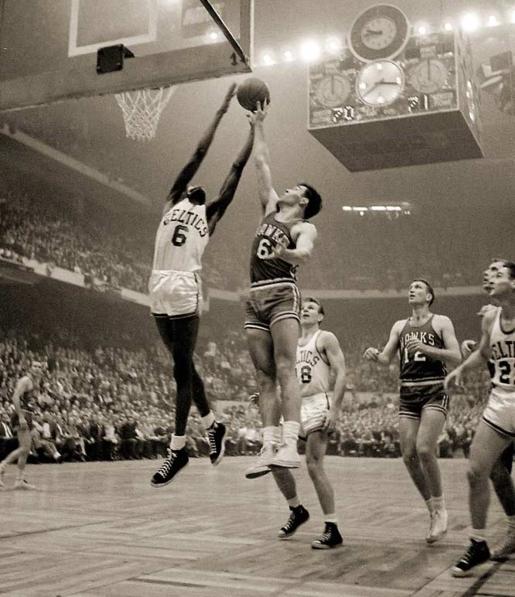

On the day of the 1956 National Basketball Association (NBA) Draft, Boston Celtics general manager (and coach) Arnold “Red” Auerbach made one of the greatest trades in NBA history. He dealt All-Star Center Ed Macauley and rookie small forward Cliff Hagan (drafted by the Celtics in 1953 but never played for the team as he remained at the University of Kentucky for one more season and then spent two years in the military) to the St. Louis Hawks for University of San Francisco center Bill Russell, who had been selected with the second pick in the draft. Macauley and Hagan were both great players (they are both in the Basketball Hall of Fame), but Bill Russell was one of the greatest players of all-time and led the Celtics to a remarkable eleven championships in his thirteen seasons in the NBA (amusingly, one of the only years he failed to win the title was in 1958 when he and the Celtics were defeated in the NBA Finals by none other than Macauley and the Hawks, which still remains the only title in Hawks franchise history).

You might have noticed, though, that the trade was for Russell after he was taken with the second pick in the draft. The Rochester Royals had the first pick in the draft. Why didn’t they draft Russell? There is a legendary story explaining why they passed on Russell. Here is Auerbach telling the story to John Feinstein in Feinstein’s 2004 collection of Auerbach stories, Let Me Tell You a Story: A Lifetime in the Game:

‘So how’d you get them to not take Russell?’

Red smiled. I had set him up perfectly.

‘The Ice Capades,’ he said.

‘The Ice Capades?’

‘Sure. Walter Brown [the owner of the Celtics] was president of the Ice-Capades. I had him call Les Harrison, the owner in Rochester, and tell them he’d send the Ice Capades up there for a week if they didn’t draft Russell.’

‘So you got Bill Russell for the Ice-Capades?’

‘You got it.’

Auerbach told basically the same story to Terry Pluto for Pluto’s classic 1992 oral history of the early days of the NBA,

Tall Tales: The Glory Years of the NBA, in the Words of the Men Who Played, Coached, and Built Pro Basketball

Listen, most people don’t know it, but we had assurances from Rochester that they would not take Russell. Lester Harrison was having trouble booking the Ice Capades. At one time, Walter Brown owned part of it. So Walter told Harrison, ‘If you pass on Russell, I’ll help you get the Ice Capades.’ That clinched the deal.

Bill Russell has told essentially the same story, as well, but he also specifically noted that it was Auerbach who told him the story much later on (as he was not privy to the details of the trade at the time).

The “Bill Russell was traded for the Ice Capades” story has now become an accepted part of basketball lore. But is it true?

Before we examine the story any further, it should be noted that Walter Brown never spoke about the incident before he passed away in 1964. Lester Harrison, for his part, vehemently denied the story before he passed away in 1997. Auerbach told the story a number of times before he passed away in 2006. So we’re dealing with a disputed story involving three deceased gentlemen. So if we can’t ask them about it anymore, what we can we do? Well, we can look at what the situation was in April of 1956 and determine how credible the story is. The two major areas of dispute are “Is it unbelievable that Harrison would pass on Russell otherwise?” and “Would Harrison need Brown’s help to have the Ice Capades in Rochester?”

IS IT UNBELIEVABLE THAT HARRISON WOULD PASS ON RUSSELL OTHERWISE?

Here, it seems as though Harrison had a number of reasons not to draft Bill Russell.

First off, you have to understand the differences between the various owners in the NBA in 1956. The league was formed by a 1949 merger between the Basketball Association of America (BAA) and the National Basketball League (NBL). The biggest difference between the leagues was that the BAA was formed by arena owners looking to get more use out of their arenas (Walter Brown, for instance, owned the Boston Garden) while the NBL was formed using semi-pro corporate teams that rarely played in arenas. The Rochester Royals, for instance, began life as a semi-pro team representing Seagram’s distillery (they called themselves the Rochester Seagrams). Lester Harrison was the coach and general manager of the team for many years and did a wonderful job with the assets he had. After World War II, the NBL was looking to expand and Harrison’s Rochester squad was one of the teams that they wanted to add. Harrison had already split with Seagram’s in 1945 over his decision to make the team a full-time professional squad (they did not believe that the endeavor would be profitable) and he joined the NBL in 1946 (Harrison’s brother Jack helped co-found the team). Unlike some of his opponents, Harrison did not own his own arena. The city of Rochester owned the arena that they played in (the Edgerton Park Arena, an arena so small that Rochester could not have a hockey franchise until Rochester built a modern arena, the Rochester Community War Memorial, in 1955). The owners who came to the NBA from the NBL tended to be small-time businessman striving to keep up with their much richer opponents. Even before the 1956-57 season, the other NBA owners had been pressuring the smaller teams to move to bigger cities (Ben Kerner had already moved the Hawks from Milwaukee to the bigger market of St. Louis just a year earlier). Of the five NBL teams that survived the NBL/BAA merger, remarkably all five moved within a decade of the merger. So in an era before television opened up a whole new revenue stream, attendance was the way that teams would make money and Rochester drew poorly (they had the worst record in the league, so it is not a surprise). It is important, then, to note that Harrison was strapped for cash going into the 1956 NBA Draft.

Money was a major factor with regards to the drafting of Bill Russell. Abe Saperstein’s Harlem Globetrotters were very interested in signing Russell themselves, and the popular barnstorming exhibition team was doing much better financially than any NBA franchise was in 1956, so they had a lot more money to spend on the top African-American players in the game. The rumor (almost certainly propagated by Saperstein himself in an attempt to scare off NBA teams) was that the Globetrotters were prepared to offer Russell $50,000. In truth, they had really only offered him $15,000 (eventually upping their offer to $17,000) but the rest of the world did not know that. With an offer so large, NBA teams were justifiably worried about spending a top draft pick on a player who would eschew the NBA for the Globetrotters. What Harrison and most other NBA owners did not know, though, was that Russell was never going to play for the Globetrotters. For a player as competitive as Russell was, not playing in the NBA was likely never really an option but in a 1958 Sports Illustrated feature on Russell by Jeremiah Tax, Russell gave an even greater reason why he would never play for the Globetrotters:

Saperstein came to see me and my coach, Phil Woolpert. He just said hello and goodby [sic] to me. All the time he was there he talked to Woolpert. He told Woolpert what he could do for me and how much money I’d make and all that jazz. He never said a word to me. He treated me like some kind of idiot who couldn’t understand what the conversation was all about. I made up my mind right then that I’d never play for him….

Harrison did not know this. Auerbach, though, did (if he did not know the exact specifics of the exchange, he knew enough from sources in California, like former Celtic Don Barksdale who had retired to San Francisco and was friends with Russell’s family, that the Globetrotters were likely not a real contender for Russell). Moreover, Harrison actually did meet with Russell and Russell informed him that it would take $25,000 to get Russell to play in Rochester (Russell was also irritated that Harrison brought along a former African-American player of his, Dolly King, to his meeting with Russell. It likely reminded him of his Saperstein meeting). He might as well have been asking for $250,000, as Harrison would be extremely hard pressed to pay that sum (later, Hawks’ owner Ben Kerner said as much about the chances of the Hawks also being able to afford Russell themselves had they kept the second pick). Russell ended up signing with the Celtics for roughly $22,000 (pro-rated for time Russell missed in his first season).

Next, while money was clearly a major factor, so, too, were the doubts about Russell’s game. It is not that people did not believe that he was going to be a good NBA player, as that much was obvious. He had led the University of San Francisco to back-to-back NCAA championships and 55 straight victories.

However, going along with the money issue, the question was whether he was good enough to be paid as much as the very best players in the NBA, players like George Mikan and Bob Cousy (which is where he would be if he made $25,000). After all, Russell’s greatest skills were as a defender and defense was not as much of a priority for big men back in 1956. College scouting was much different back then, as well. Games were not televised and teams could not afford extensive scouting, especially for players on the west coast. One of the biggest showcases for college talent was the annual East versus West All Star Game at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Russell did not play especially well at these tournaments. Even Auerbach noted that his files on Russell at the time said that Russell’s best comparison was to New York Knicks’ center Walter Dukes, a frequent comparison for Russell at the time in NBA circles. Dukes had been a top draft pick in the 1953 NBA Draft and had not done much to impress so far during his career (he had a bit of a resurgence a few years later for the Detroit Pistons, by which time he had already played for three teams in the NBA). Later on, Harrison would become convinced that Russell intentionally played poorly at the showcase games to keep the small market teams away from drafting him.

Also, while not nearly as big of a concern, Russell was very vocal about representing his country in the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. That would not normally be a big deal, except that in 1956, since the Olympics were held in Australia, the events took place in November instead of July or August. Since Avery Brundage, longtime President of the International Olympic Committe (IOC) had strict rules about amateurs competing (rules that were not exactly based in the actual history of the Olympics), Russell would not be able to sign a contract until after the Games were over to maintain his amateur status. So not only would you not have your top draft pick for a third of the season (that is why Russell’s first Celtics contract was pro-rated), but you wouldn’t even get a chance to sign him until after the Olympics finished (and again, the specter of the Globetrotters swooping in to sign him away still loomed – in fact, they made one more attempt to sign Russell after the Olympics, offering him $32,000. He passed).

Finally, the last (and perhaps the most notable) reason Harrison would be willing to pass on Russell was that the Royals already had a great center. Maurice Stokes was the second pick of the previous NBA Draft and had just won the NBA Rookie of the Year. Nearly thirty years later, the Portland Trailblazers passed on Michael Jordan because they already had Clyde Drexler, so the notion of an NBA team passing on a great prospect because he duplicated a player they already had on their team is a well-established one in NBA history. Stokes tragically suffered a brain injury during his third season in the NBA (he was an All-Star in all three seasons) that ended his career and ultimately his life in 1970. However, in 1956, he was a clear stud player and made the idea of spending so much money on another center seem perhaps not a good idea.

Ultimately, the Royals drafted a well-regarded first team All-American guard/forward from Pittsburgh’s Duquesne University, Sihugo Green. Green had a respectable eleven-season career in the NBA but was never an All-Star (and he was particularly unproductive for Rochester as he dealt with injury problems in his first and second seasons, ending up only playing in 33 games for the Royals before he was dealt to the Hawks).

Given their financial situation and the fact that they already had Stokes on the team, it seems realistic that the Royals would pass on Russell. However, what about the Ice Capades angle?

Go to the next page for the rest of this story…

Pages: 1 2

Tags: Bill Russell, Boston Celtics, Harlem Globetrotters, Ice Capades, Lester Harrison, Red Auerbach, Rochester Royals, St. Louis Hawks, University of San Francisco, Walter Brown

[…] an in-depth look into the trade-tale by Bill Cronin, he […]

Bill,

I believe that the way the trade went down was Macauley and Hagan to the Hawks for Russell (by pre-arrangement) after the Hawks had drafted Russell at number 2, rather than the Celtics simply trading for the Hawks’ number 2 pick. This suggests that Auerbach feared that the Royals might take Russell, in which case the Hawks pick would hardly be worth Macauley and Hagan. This caution on Auerbach’s part suggests there was no “Ice Capades” deal in which Rochester had agreed to pass up Russell. So this is further support for your conclusion.