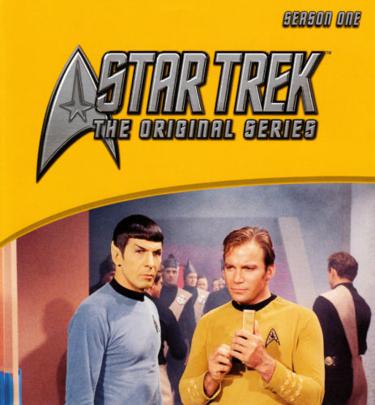

Did Martin Luther King Jr. Keep Nichelle Nichols From Leaving Star Trek After the First Season of the Show?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about TV and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the TV urban legends featured so far.

TV URBAN LEGEND: Did Martin Luther King Jr. keep Nichelle Nichols from leaving Star Trek after the first season of the show?

One of the things that we often overlook with regards to television audiences, especially in the modern era of channel diversification where there are so many more cable channels with original programming that the percentage of the viewing audience that even the most popular shows receive is seemingly quite small, is that even the least popular television shows on the non-cable channels are still seen by a relatively large amount of people. The recently canceled television drama Zero Hour, which had the worst debut of a scripted television program in ABC history, was still seen by over six million people! So as a result, it is quick to forget that even when your show is struggling in the ratings it is still reaching a large audience and possibly having a major effect on them. This is what Nichelle Nichols…

learned in 1967 when she decided to leave Star Trek after the show’s first season

only to be talked out of it by a very famous fan of the show that she never knew watched the series…Martin Luther King, Jr.!

Read on to see how it happened…

Before she was cast on Star Trek, Nichelle Nichols was best known for her work as a singer. She toured with both Duke Ellington and Lionel Hampton and their respective bands. She also did a number of notable musical theater performances, including a West Coast production of the then-new musical The Roar of the Greasepaint—the Smell of the Crowd (where the pop standard “Feeling’ Good” came from). In 1964, she was cast in an episode of the TV series The Lieutenant (about a group of Marines in what was still then-peacetime), the first television series produced by Gene Roddenberry. Sadly, the episode Nichols appeared in (where she played the girlfriend of a white Marine, a pairing to which another Marine, played by Dennis Hopper, objected) was never actually broadcast because NBC found the topic too controversial to air. Years later, Roddenberry recalled his problems with that episode having an influence on his decision to make Star Trek as diverse as he could.

In any event, when it came time to cast his new series, Star Trek, in 1966, Roddenberry recalled Nichols and wanted her for the role of the chief communications officer. The role was originally written for a man, but Roddenberry felt it proper to have at least one of the department heads on the starship Enterprise be a woman. As a demonstration of what the atmosphere was like at the time, Desilu producer (Desilu Studios produced the first season of Star Trek) Herb Solow remarked in a 1967 Ebony interview that they were surprised by how good of an actress Nichols turned out to be, noting that they were only looking for a “shapely broad.”

In a wonderful interview with the Archive of American Television, Nichols explains that once filming completed on the first season of Star Trek, she had a contract offer for the second season but she had also received an offer to do a play that was headed toward Broadway. Since that had always been her passion, she decided that she would resign from Star Trek and pursue this new theater offer. Nichols specifically recalled the fact that they never told the stars on the show just how much fan mail that they each had been receiving, so she had no real idea that the show (which never did particularly well in the ratings during its three seasons, although the ratings problems in the first season have likely been overblown a bit) had such a rabid fan base. Heck, Nichols recalled that she rarely even saw the show when it aired, as she was often out at night.

When she informed Gene Roddenberry that she wished to resign from the show, he tried to talk her out of it, telling her that her role on the series was an important part of his vision. He requested that she take the weekend to think it over. The first season of Star Trek finished filming on Wednesday, February 22nd, 1967. So their meeting took place on either that Thursday or that Friday. She agreed to take the weekend to think things over. That Saturday, February 25th, Nichols attended an event at the Beverley Hills Hilton. Decades later, Nichols does not recall the specific event she was attending (recalling it was likely a NAACP fundraiser), but as it turns out, the event was a major point in the history of the anti-Vietnam War movement. You see, while famed Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. never supported the Vietnam War, it was not until his speech at the Beverly Hills Hilton on February 25th (in connection with the Nation Institute, as King was a contributor to progressive magazine The Nation) that King roundly came out against the Vietnam War and specifically began to tie the Civil Rights movement together with the Anti-War movement. Here is a snippet from King’s classic speech, “The Casualties of the War in Vietnam”

I oppose the war in Vietnam because I love America. I speak out against it not in anger but with anxiety and sorrow in my heart, and above all with a passionate desire to see our beloved country stand as the moral example of the world. I speak out against this war because I am disappointed with America. There can be no great disappointed with our failure to deal positively and forthrightly with the triple evils of racism, extreme materialism and militarism. We are presently moving down a dead-end road that can lead to national disaster.

It was at this event that Nichols was told that a fan of hers wanted to talk to her. She waited while the fan came over. As you might have guessed, the fan turned out to be Dr. King himself. He told her how much he loved her and Star Trek and how it was the only show that he and his wife Corretta would allow their two young children to stay up late to watch. She thanked Dr. King and told him how much she’d miss the show and her co-stars. King was taken aback and told her “You cannot!” Nichols, naturally, was taken aback herself. He continued to tell her that she had to realize how important Roddenberry’s message was, telling her “for the first time on television, we are seen as we SHOULD be seen,” explaining that she was a role model for her people, as her role was not a “black” role, it was a role that African-American actors and actresses normally would never get. He continued with the powerful line, “Gene Roddenbery has opened a door for the world to see us. If you leave, that door can be closed.” Nichols took his message to heart. She spent Sunday actually somewhat irritated at the situation, essentially asking the question, “Why me?” However, on Monday she went back to Roddenberry and asked for her resignation letter back.

Years later, the first female African-American to reach outer space, Mae Jemison, would specifically cite Nichols’ influence upon her career choice (Jemison appeared in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1993, a year after she became the first African-American woman in space).

The legend is…

STATUS: True

Thanks to reader Jim S. for suggestion this one and thanks to the Archive of American Television and Nichelle Nichols for the information.

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future installments! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com.

Tags: Star Trek

Good story. However, “Star Trek” aired on Thursday nights from 8:30 to 9:30 (ET) in its first season, not from 9 to 10. Here’s the 1966-67 prime-time schedule:

http://classic-tv.com/schedules/1966-1967-tv-schedule.html

Also, the episode of “The Lieutenant” you wrote about was never aired until TNT ran it in the early 1990’s.

Thanks, Patrick, I just dropped the time slot info entirely.

I’d be wary of trusting Nichelle Nichols’ version of that story, at least for the specifics. I used to read a lot of nonfiction about Star Trek, and in the course of that reading, I read three different accounts from Nichols about Martin Luther King telling her not to quit the show. In one account, he sent her letter, in another, he called her on the phone, and in another, he spoke to her in person. So while it’s probable that there was some contact in one form or another, it does seem pretty likely that this may have been one of those “fish stories” that grew in the telling as time went by, and I’d be careful about recounting Nichols’ current story as definitely true without outside verification.

I wouldn’t be surprised at all if she was embellishing the tale a bit, but the timeline of events fits so well with her version of the tale (his speech being in Los Angeles the weekend after they finished filming Season 1 of Star Trek) that it lends her story a lot of credibility. Most BS stories of the kind don’t get facts like that correct. But sure, it wouldn’t be surprising at all if his comments were not quite as effusive as Nichols describes.

Regarding the episode of “The Lieutenant” (titled “To Set It Right”, according to Wikipedia) NBC not only refused to broadcast the episode, they refused to pay for it as well. That forced the production company (MGM television) to eat the episode’s expenses.

One reason that Gene Roddenberry may have remembered Nichelle Nichols for “Star Trek” is that he was (allegedly) having, or had, an affair with her. I’m not clear on the timeline for the alleged affair, however.

[…] The first female African-American to reach outer space, Mae Jemison, would specifically cite Nichols’ influence upon her career choice (Jemison appeared in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1993, a year after she became the first African-American woman in space) (x) […]

[…] […]

[…] The first female African-American to reach outer space, Mae Jemison, would specifically cite Nichols’ influence upon her career choice (Jemison appeared in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1993, a year after she became the first African-American woman in space) (x) […]

Sadly, I do not believe the MLK story.

In 2010, Nichols gave a very elaborated account to an interviewer, now including for the first time the new detail that she told Gene Roddenberry all about the encounter the day after it happened. She says he was moved to tears and there’s a dramatic bit about the production of the letter of resignation, a plot device straight out of The Princess Bride (the novel).

http://planetwaves.net/news/daily-astrology/martin-luther-king-mlk-uhura-nichelle-nichols/

So why did Roddenberry never tell the story while he was alive? It’s quite a tale and fits perfectly with Roddenberry’s vision. He was a storyteller and he would have jumped on this perfect, too perfect, story.

Likewise, I don’t believe Nichols’ claim that she and Roddenberry had an affair. Once again, this story came out only after Roddenberry had passed and no one had ever suspected any such thing till then. I’ve heard stories of other Roddenberry affairs, but no one has ever suggested that discretion and secrecy ever figured in any of them.

Expecting her any day to seek fresh ink with a brand new and completely unverifiable story about Nimoy.

Of course, this takes NOTHING away from the fact that Uhura was and is an inspirational breakthrough. Nichols gave a great performance and it’s wonderful that it inspired Mae Jemison. But it’s sad that Nichols thinks she needs fiction to embellish her very real accomplishment.