How Did a Professional Wrestling Promoter Saved the Montreal Canadiens (and Helped Form the NHL)?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about hockey and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the hockey urban legends featured so far.

HOCKEY URBAN LEGEND: A professional wrestling promoter ended up securing the Montreal Canadiens’ place in professional hockey history.

Les Canadiens de Montréal (otherwise known as the Montreal Canadiens) are the most successful team in the history of professional hockey. They have won the Stanley Cup a record twenty-four times (twenty-two since the Cup has been awarded to just the winner of the playoffs of the National Hockey League, before that, multiple leagues would compete for the trophy). They are the only original member of the National Hockey League (NHL) that is still playing today and are also the only team that pre-dated the founding of the NHL.

And yet, if it were not for a professional wrestling promoter, they likely never would have lasted five seasons, and we might never have had an NHL!

Read on to discover the amazing role that former professional wrestler George Kennedy played in the existence of Les Canadiens de Montréal and the formation of the NHL!

The Montreal Canadiens (as I’ll be referring to them from here out, just for simplicity’s sake) were formed in 1909 as part of political in-fighting in the Eastern Canada Hockey Association (ECHA), a professional hockey league of the time. You see, P. J. Doran, owner of the Jubilee Rink in Montreal, had just purchased the Montreal Wanderers, one of the teams in the ECHA. Doran, naturally, purchased the Wanderers so that they would become the star attraction of his arena. The other ECHA teams hated this idea, since the Jubilee Rink was much smaller than the Wanderers’ current home, the Montreal Arena and therefore their cut of the gate receipts would be considerably smaller.

So the other owners voted to dissolve the ECHA and form the Canadian Hockey Association (CHA) with three other Montreal teams (one, the Montreal Shamrocks, already existed, plus two new ones, All-Montreal, formed by Wanderers star Art Ross and Montreal Le National, an all-French speaking team) taking the place of the Wanderers (they actually gave the Wanderers a chance to join the new team, but only if they agreed to go back to the Montreal Arena. Doran, as you might imagine, did not agree to those terms).

Meanwhile, Ambrose O’Brien, a silver mining industrialist from Renfrow, Ontario, was in town to petition the ECHA to allow his hometown team, the Renfrew Creamery Kings, to join the ECHA. They turned him down. At that same meeting, though, O’Brien encountered Doran, and the two men agreed to form their own professional league, the National Hockey Association (NHA)! O’Brien owned two small pro teams in Ontario (in the mining towns of Cobalt and Haileybury, respectively) and with the Creamery Kings (it is unclear to me if O”Brien owned the Creamery Kings before 1909 or if he was just working on their behalf – whichever the case may be, by 1909 he was the owner of the team) and the Wanderers, they made up the new league. Doran, though, suggested that the CHA’s idea of a French-speaking team was a good one, and that O’Brien ought to start one so that there could be a strong rivalry in Montreal between the English-speaking Wanderers and the new French-speaking team. O’Brien agreed, and he formed the Montreal Canadiens. Right from the start, O’Brien was not particularly interested in the Canadiens, as he had three other teams to worry about (and he only really cared about the Renfrow team), so after the inaugural NHA season, he wanted to find someone to take the Canadiens off of his hands. He got his wish, but it came under unusual circumstances from a man whose whole life was unusual – George Kennedy.

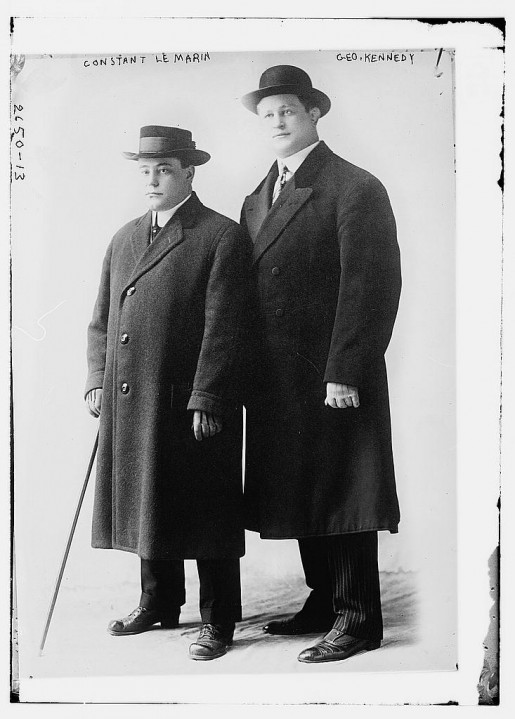

George Kennedy was born George Washington Kendall in 1881 to an Irish-Catholic mother and a Scottish-Quebec Baptist father. Raised Catholic, Kennedy was also (like many Montreal residents) bi-lingual, speaking English and French. Despite coming from a well to-do family (his father owned a successful manufacturing business), George decided that he was going to be a professional wrestler! Having some sense of how this would look for his family, George took the stage name of George Kennedy, which is the name he would use for the rest of his life.

By the early 20th Century, Kennedy was the top lightweight wrestler in all of Canada. In 1903, he was defeated by Eugène Tremblay. Upon his defeat, he decided to change careers and instead become a wrestling trainer and promoter. His first client? Why, Eugène Tremblay, of course! In 1905, Tremblay won the world lightweight championship over the American George Bothner (naturally, Kennedy made sure that the match was held in Montreal). Using the success he had with Tremblay as a springboard, later in 1905 Kennedy formed (with his good friend, Joseph-Pierre Gadbois, who had been Kennedy’s> trainer) Le Club Athletique Canadien (CAC) where amateur wrestlers could train (soon they added amateur boxers, as well). The bi-lingual Kennedy was well acquainted with the fervor of patriotic French Canadian pride that existed in Montreal, and that is where he geared the CAC’s efforts (when he incorporated the club, most of its shareholders were French-Canadians).

As Kennedy expanded the CAC, he continually looked for new sports to get involved in. By 1908, he was interested in purchasing a hockey team. He tried to buy the Wanderers, but was rebuffed. At the time, Kennedy spoke of having a team that he could gear toward French-Canadians, so you can just imagine his irritation when not only pro one hockey league in 1909 came up with the same idea, but both pro hockey leagues! So by the end of the 1909-10 season, he was bound and determined that one way or another, he was going to own the Montreal Canadiens.

Meanwhile, the CHA was not doing too well. They ended up having to fold before the 1909-10 season even finished. They unsuccessfully tried to get the NHA to merge with them (as you might imagine, trying to get fans to come to five different pro hockey teams in the same city in the same year was not easy to do). Instead, the NHA absorbed two teams from the CHA (Ottawa’s team and the Montreal Shamrocks) into the NHA for the rest of the 1909-10 season, giving the NHA seven teams. O’Brien offered the Canadiens to the CHA’s French-speaking team, Montreal Le National. but they refused to play in the Jubilee Rink, so that deal fell through.

During that same 1909-10 seaso, O’Brien was determined to see Renfrew win the Stanley Cup, and even sent the Canadiens’ best player, Édouard “Newsy” Lalonde, to the Renfrew team (now referred to as the Renfrew Millionaires, due to the amount of money O’Brien was spending on players) to help them win. Instead, despite owning four of the seven teams in the NHA, none of O’Brien’s teams won. Instead, the Montreal Wanderers were the champions of the first NHA season. The Canadiens, by the way, were the worst team in the league, going 2-10. After the 1909-10 season, the Cobalt and Haileybury teams were dropped (even in 1909, cities that small just could not support professional teams).

Here is where things get tricky, and records are disputed. It is agreed that Kennedy, determining that the best way to make sure O’Brien would sell him the Canadiens (with Kennedy not knowing that O’Brien was trying to get rid of the team), sued O’Brien for trademark infringement, claiming that Les Canadiens de Montréal (yes, I know I said I would just call them the Canadiens, but it makes more sense as a possible infringement if I used the official name) infringed on his trademarked Le Club Athletique Canadien.

It is also agreed that Kennedy then did take over as the owner of the Canadiens for the 1910-11 NHA season.

What is disputed is how it happened. History has generally told us that the suit was settled by Kennedy paying O’Brien $7,500 for the rights to the team (O’Brien himself told this version of the story). However, in their brilliant 2002 book, Deceptions and Doublecross: How the NHL Conquered Hockey, Morey Holtzman and Joseph Nieforth argue that O’Brien simply said, “Okay, take it, it is yours” when Kennedy sued him, since the Canadiens were losing money for O’Brien and he never wanted the team in the first place. Their position is that the $7,500 figure came not from Kennedy buying the rights to the team, but from buying the rights to Newsy Lalonde, who was now on the Renfrew team (and O’Brien was not going to give him up so easy). From the circumstances of the times, I tend to believe Holtzman and Nieforth.

In any event, Kennedy was now the owner of the Canadiens (who he re-named Club Athletique Canadien, although everyone kept calling them their old name) and the team began to perform better. O’Brien, meanwhile, could no longer afford to stick around in the pro leagues, and he (and Renfrew) exited the NHA after the next season.

Kennedy continued to vary his sporting enterprises, and had a particularly notable 1915-16 season. In 1915, he purchased the rights to distribute the film of the 1915 World Heavyweight Boxing Championship (where Jack Johnson was dethroned). Kennedy had been trying to get boxing legalized in Montreal for years, and in early 1916, after a complaint from Canadian Vigilance Association led to Kennedy having to appear in municipal court, he finally succeeded in officially legalizing the sport in Montreal. He capped it all of by seeing his Montreal Canadiens win their first Stanley Cup in 1916.

However, his expansions also began to stretch his finances (including a professional baseball team), especially when he tried to start a professional lacrosse league, the Dominion Lacrosse Union, including his Montreal Canadiens lacrosse team. Plus, in 1916 the CAC’s home gym burned down. Kennedy regrouped and formed a new streamlined organization, the Canadian Hockey Club Incorporated, which obviously was spotlighting the hockey team, although he continued to promote wrestling and hockey, as well (not so much his other sports – heck, Kennedy once tried to bring bullfighting to Montreal!).

Around this same time, history repeated itself when a bunch of NHA owners had a number of disagreements with the owner of one of the franchises they had added as the league had expanded (in part to replace O’Brien’s departure), Eddie Livingstone’s Toronto franchise. In 1917, led by Kennedy and the owners of the Ottawa and Quebec franchises, the NHA voted to disband and re-form (without Livingstone) as the National Hockey League. They did not intend for it to be a full-time thing (figuring that they would force Livingstone to sell and then the NHA would reform), but that’s exactly what it ended up being, as the NHL is still standing today.

In the second year of the new league, Kennedy’s Canadiens won the NHL championship and were in the middle of the Stanley Cup finals (then played between the winner of the NHL championship and the winner of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) championship) against the PCHA champs, the Seattle Metropolitans. The series was headed into its deciding game when the influenza epidemic of 1918-1920 led to the entire Canadiens team coming down with the flu. Health officials canceled the rest of the series. Four days later, Canadiens defenseman Joe Hall died of the disease. Kennedy never fulled recovered from the flu and died in 1921. His widow sold the team to Montreal businessmen Joseph Cattarinich, Leo Dandurand and Louis A. Letourneau. The Canadiens won their first NHL Stanley Cup in 1924.

And then, you know, about a gazillion more Stanley Cups.

And it can all be tracked back to a professional wrestler from Montreal!

The legend is…

STATUS: True

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future urban legends columns! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com