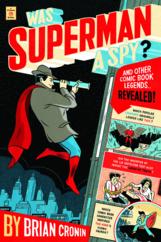

Was Judy Garland Paid Less for the Wizard of Oz Than the Dog Who Played Toto?

Here is the latest in a series of examinations into urban legends about movies and whether they are true or false. Click here to view an archive of the Movie urban legends featured so far.

MOVIE URBAN LEGEND: Judy Garland was paid less for The Wizard of Oz than the dog who played Toto in the film.

One of the most dispiriting pieces of news that came out as a result of the hack that Sony suffered last year is that there was noticeable wage disparity at Sony between male and female workers, from the female Co-President of Columbia Pictures, Hannah Minghella, making almost a million dollars less than her male Co-President, Michael De Luca to the two female leads of American Hustle (Amy Adams and Jennifer Lawrence) each getting paid less than the three male leads of the film (Christian Bale, Jeremy Renner, Bradley Cooper) and director David O’Russell. If this was the case nowadays, you can only imagine what kind of out of whack scale there was for actors back in the old days, when actors signed long term contracts with studios, locking in their pay rate early in their careers. So actors, especially actors just starting out, were paid some surprisingly low wages on famous films. This had led to a few legends over the years, perhaps none more notable than the story that Judy Garland, star of the 1939 classic film, The Wizard of Oz, made less money during the film than Terry, the dog that played Toto in the film.

The exact figures that often make the rounds of the internet is “For the movie the Wizard of Oz, Judy Garland was paid $35 a week while Toto received $125 a week.”

Is that true?

In a lot of ways, the making of The Wizard of Oz (which was about Dorothy, a young farm girl from Kansas who travels to the wonderful world of Oz during a tornado, where she befriends a talking Scarecrow, a Tin Man and a Cowardly Lion, all while trying to get to the Wizard of Oz so that he can send her back home before the Wicked Witch of the West gets her revenge on Dorothy for accidentally killing her sister, the Wicked Witch of the East, when she landed in Oz) was a perfect encapsulation of what it was like to make major motion pictures at the studios back in the 1930s.

As I noted in an old Movie Legends Revealed, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) wanted Shirley Temple for the role of Dorothy but Temple was under contract to 20th Century Fox, so the only way that they would be able to get Temple was to make a trade of one of MGM’s actors for Temple. They were unable to work out a deal, so they instead went with their original choice, a promising young actress that they had already signed to a deal, Judy Garland.

Garland was treated like a piece of meat on the set, with director Victor Fleming (the fourth director to work on the film!) even slapping her when he felt it was necessary to get her to give a certain performance, while the studio forced her to practically starve herself to keep herself skinny (often resorting to smoking dozens of cigarettes a day to keep her mind off eating). It’s fairly remarkable that she was able to give such a magnificent performance in the film under the circumstances.

But was she also paid less than the dog?

That, at least, was not the case.

Garland was paid $500 a week on the production, while Terry, the 5-year-old Cairn Terrier (Terry was born in 1933, but I don’t know when in 1933, so she was between 4 and 5 years old while filming the movie in 1938) was paid $125 a week. Interestingly enough, there was such a desperate search for a dog that looked like Toto as Terry did that Terry’s owner and trainer, Carl Spitz, likely could have held out for more had he known how desperate the studio was (Terry was the last of the main cast to be cast for the film).

Like most of the actors, Terry was injured during the production of the film (one of the extras stepped on her paw during a scene) and Terry stayed with Garland while recuperating. Garland grew so close to Terry that she begged Spitz to let her adopt her. Spitz naturally enough said no.

Garland’s pay rate was significantly lower than her co-stars, though, as Scarecrow Ray Bolger and Tin Man Jack Haley were each making roughly $3,000 a week. The lowest salaries on the film were for the actors who played the Munchkins, as they each got paid less than Terry ($100 salaries, but with their manager, Lew Singer, getting a 50% commission on their pay).

The legend is…

STATUS: False

Thanks to my buddy Eric Gjovaag, and his excellent Wizard of Oz website, for the information. Eric wished to credit Aljean Harmetz’s book “The Making of The Wizard of Oz,” as his source. Thanks again, Eric!

Feel free (heck, I implore you!) to write in with your suggestions for future installments! My e-mail address is bcronin@legendsrevealed.com.

Heh, yup, all true—but you’ve made one little error. While Toto, the character, was male, Terry, who played him, was female. You’ve referred to her as “he” a few times up there. She became so well known for the part that her name was changed to Toto after the movie’s release. (Now feel free to do a legend on her final fate…)

It was just once! 🙂 I know Terry is a she (and I called her “she” and “her” in the piece), but you’re right, I did drop a “he” in there once. I think I just accidentally dropped the s!. 😉 Fixed now! Thanks for the head’s up, Eric!

Everyone be sure to check out Eric’s amazing Wizard of Oz website, http://thewizardofoz.info!

I should probably also mention MY source for the information, and that would be Aljean Harmetz’s exhaustively researched book “The Making of ‘The Wizard of Oz'”. It first came out in the late ’70s, in celebration of the movie’s fiftieth anniversary, but it’s still available (with some additional material) today.

D’oh! Just looking back, I found an error in my own comment. The original publication of “The Making of ‘The Wizard of Oz'” was in celebration of the movie’s FORTIETH anniversary, not fiftieth. An expanded edition did come out for the fiftieth in 1989, however. And it is still in print, in time to celebrate the movie’s eightieth anniversary this year (and thus, the book is now celebrating its fortieth).